Simon Parker on the future of government: Complex problems, systems thinking, and a reframing of…

Or: why — and how — good policies create “places” worth living in

Today, the @staatslabor shared an article by Simon Parker. As they wrote: Read Simon’s essay. Really. It’s good. I trust them (really!) and so I jumped right into reading it (bye-bye productivity!) And indeed: What Simon wrote instantly struck a chord (well, four) with me.

In fact, it was so good, it sent me down a rabbit hole and prompted me to write this post, theorizing on the following:

Good policies create “places” worth living in.

So, here are some ideas on how to approach policy design with insights from architecture and systems thinking, and how this might lead to better policies.

Public service is about highly complex problems

In his article, when talking about agile and design thinking in government, Simon sums up nicely what I somehow always felt but never could articulate, and definitely not so succinctly:

A lot of people have gotten stuck [when applying agile and design thinking in government]. They […] discover powerful ways to create human-centred services, but then cannot understand why the world isn’t changing. The answer is simple: public service isn’t really about services, but about highly complex problems.

Once you look at it this way, you can recognize that many innovation initiatives in government stop exactly there: With new innovation methods, agile project management. Of course, I’ve been guilty of that innovation frenzy too, and mileage certainly varies wildly across initiatives. You need tools — methods and management practices — that help civil servants and their organizations break out of old habits, that help them redesign services that work and appeal to citizens. But these are not enough.

So how can public service approach these highly complex problems? What would public service have to look like?

A new purpose for public service?

In the article, Simon does an excellent job in describing many of the changes we are about to witness, and why systems thinking concepts might be a natural next step after agile and design thinking. And he outlines a proposal for a new purpose for future government:

“Government should aim to maximise self-organisation.”

This struck a second chord: Here in Switzerland, policy and governance are generally understood to be about creating good (excellent) boundary conditions — and to let the people and organisations then fill the space that these boundary conditions create with life; to use it for their goals and ambitions (or needs). “Adult-adult mode”, as Simon also calls it.

(N.B.: I have yet to hear someone argue that the public management approach in Switzerland “maximises self-organisation”, but there is something to that idea — some similarities, but also some differences. I won’t go into these today.)

I also couldn’t agree more with Simon that the 12 leverage points of Donella H. Meadows provide a lot of food for thought to think about the “Where” to intervene in the system.

Yet, both the concept of systems thinking and the idea of leverage points say little about “How” governments could aim to maximise self-organisation.

Where agile and design thinking are both practical methods, systems thinking is obviously a concept, a school of thinking and a way to look at the world — and so it needs its own practical language, methods and heuristics when applied to a system like a government or the “results” this government produces through its policymaking.

How to support people and organisations in self-organisation

This is where Simon’s article struck the third chord with me: Assuming there is some consensus on the “Why” — that governments should aim to maximise self-organisation — the question we then must ask is the following:

How can governments (or civil servants, to be precise) design policies and policy interventions in a way that optimally support people and organizations in maximising their respective amount of self-organisation?

I don’t have much of an answer yet to this “How” (and I am looking for any hints and inspiration and food for thought), but my fascination with architecture — and its approach to design — has recently led me down a rabbit hole of thought, which I already wrote about elsewhere.

There, I argued that architectural patterns and theory of architectural design might serve as inspiration for tackling policy design and the kind of complex problems public service deals with.

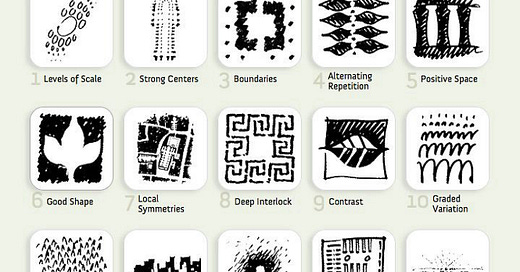

In a nutshell, I think that Alexander’s 15 fundamental properties of well-architected systems are a high-level pattern language that we can use when working on policy design. And so we can apply them when thinking about how governments can optimally support the aim of maximising self-organisation — both within the public service (the bureaucracy) and when the public service is designing policies and policy interventions.

I am deeply convinced that precise, well-crafted language has the power to transform systems at large, even defying strategy, structure and even culture.

By using the fundamental properties as such a shared and precise language — by defining carefully what the language means when used in policymaking — we might have a very powerful instrument at our disposal, one that can help with better policy and systems design.

But what can we do now?

To this point, we have, together with Simon, been looking at a potential “Why” of future governments — the proposed aim to maximise self-organisation; and we have had a peek at “How” this could be achieved, potentially, by using the pattern language of Christopher Alexander’s fundamental properties as a new tool in our design of policies.

What we haven’t answered yet is the “What” that inevitably follows these two questions: What could we do now?

A natural answer (one, I must admit, that I’ve entertained as well in the past) could be to disrupt the state, to “tear bureaucracies apart” — or, as Schumpeter declared for economics: to transform the state through creative destruction.

But is it a good answer? Rainer Kattel (among others) doesn’t think so, and personally, I concur.

In his article on the Entrepreneurial State, Kattel outlined that for the state to become more agile or innovative, it is indeed popular to call for the disruption of said state. But also, that this is indeed not a new idea:

“Today’s popular call to disrupt the government through innovation is, to say the least, as old a hat as that on the head of a Renaissance soldier of fortune in an Uccello painting.”

But ultimately, he concludes that

“Capacity for innovation in bureaucracy is about having the space — skills, networks, organisations — for both agility and stability.”

And this nicely resonates with Simon again and the take-way from his debates with Enspiral:

“[Y]ou should not and cannot strive for structurelessness in organisations and society. The attempt to dismantle hierarchy often leads to new, secretive hierarchies emerging behind the scenes. The state is a hierarchy and there are some good reasons for that. Let’s not try to deny its essential nature.”

Fourth chord. But: no answer yet on how can we achieve this agility and stability. No answer how can we honour these essential structures of the organisations we’re working with and bring meaningful change to them.

Structure-preserving transformation

I would propose that one approach is to again look at Alexander’s work, specifically at his concept of “structure-preserving transformations” that he offers in “The Nature of Order”.

Nikos A. Salingaros, in Design for a Living Planet1, writes the following about this approach to design:

“This idea of design — as “transformation” using an adaptive process — is very much at the heart of […] Christopher Alexander’s work. Through that adaptive process, we generate a form that achieves our “preferred” state. But at each step of this transformation, Alexander says, we are dealing with a whole system — not an assembly of bits.” (Design for a Living Planet, Chapter 20)

Besides building on the fundamental properties, I think that Alexander’s adaptive approach of “structure-preserving transformations” offers a real answer to what we can and shall do when thinking about optimising self-organisation through the lens of the fundamental properties: to start with a (simple) system and change it in a way that preserves the structure of the previous step.

“Complex systems do not spring into existence fully formed, but rather through a series of small, incremental changes. The process begins with a simple system and incrementally changes that system such that each change preserves the structure of the previous step.” (from Wikipedia: The Nature or Order)

Agility and stability

I think the works of people like Christopher Alexander and Donella H. Meadows can offer us great insights and concepts on how to think about the systems and policies we design and interact with, and how we implement our policies.

Personally, I find the idea intriguing of a practical approach using their concepts and language intriguing. From the dancing with the system (Meadows) to the algorithms of “structure-preserving transformation” and the “language” of the fundamental properties we use as the programming language of these algorithms (both Alexander): I think their work can offer a compelling — and surprisingly precise — framework for those working in the public service, for those tasked with creating better policies or working to innovate their bureaucracies.

In the end, a policy can be considered a blueprint for a “place” of sorts. And this place — with its shape and function, with its deficiencies and strengths — is intricately linked to the way its blueprint was created, to the way the policy was designed (A bit like Conway’s Law, but with an architectural/spatial twist, if you like. But I digress).

Once the policy is implemented (when the new “place” is finally brought into existence), people and organizations will start inhabiting the place which the policy created.

If the policy embodies the idea of “structure-preserving transformations”, if it is built on sound principles of architectural design, then this policy will equally honour the past and prepare for the future. The place this creates will offer us both: agility and stability.

A place that is brought into existence through such a well-designed policy will presumably be filled with brimming life, self-organised by its “inhabitants”.

And a system transformed in such a way will indeed become a place worth living in.

The writing here is an attempt to give some much-needed structure to my thinking and solely represents my views. I look forward to exploring these thoughts and threads even more and would love to hear your remarks about that!

This post is a result of the excellent Personal Knowledge Mastery Workshop by Harold Jarche which I highly recommend to everybody interested in better managing their personal knowledge mastery.

References

“Ch 20. Alexander’s “Wholeness-Generating” Technology.” In Design for a Living Planet: Settlement, Science, & the Human Future, 198–208. Design for a Living Planet: Settlement, Science, & the Human Future. Levellers/Sustasis Press and Vajra Publications, 2015. (Original Publication: Metropolis Mag, 24 Oct 2011) ↩︎